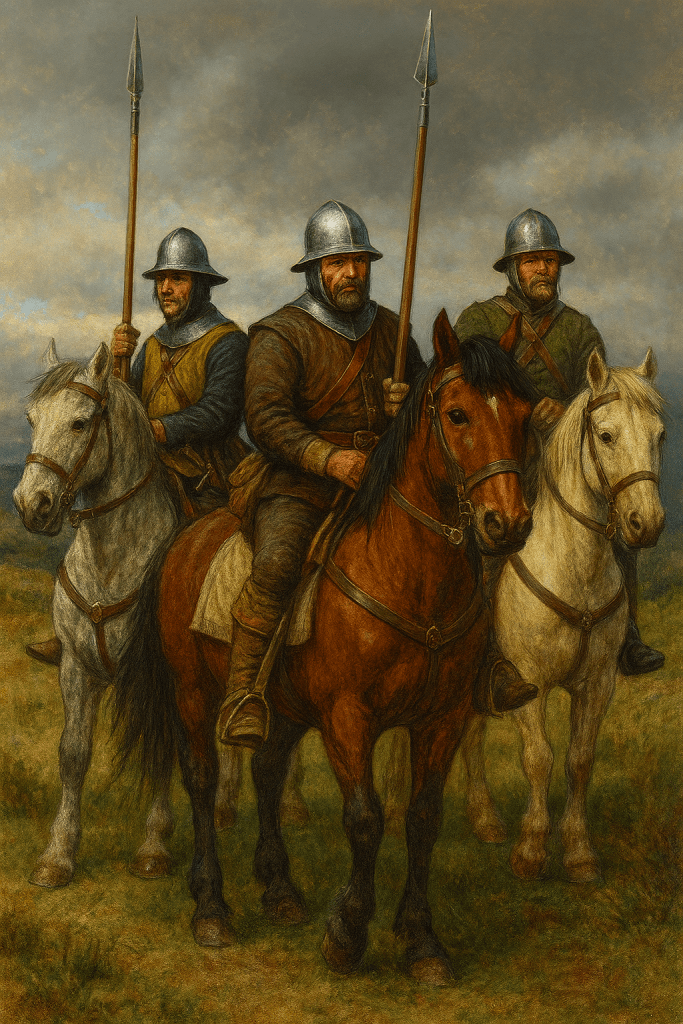

“The moon hangs low over the Cheviot Hills. Hooves drum against the frozen earth, and a line of riders slips through the mist. Their faces hidden beneath steel helmets, their cloaks keeping out the chill wind, their spears at their sides. Behind them lies Scotland; ahead, England. But in truth, they belong to neither. They are Border Reivers—products of a frontier, bound not by crown or country, but by kin and survival.”

Origins

The word Reiver comes from the old verb “to reive”, meaning “to rob or plunder.” But reducing the Reivers to mere thieves misses the complexity of their world.

The origins of large‑scale, organised reiving likely began with Edward I’s invasion of Scotland in 1296 and the Wars of Independence that followed. Campaigns such as those leading up to Bannockburn in 1314 devastated the land on both sides of the border.

The outcome for those living near the border was burnt homesteads, insecure tenure, destruction of crops and pressure on already limited good pastureland. Indeed, boggy ground, thin soils, and a harsh climate favoured livestock over arable crops, limiting the possibility of secure surplus production.

Border reiving was, in large part, an economic adaptation to these conditions. Organised stock theft and ransom became a rational way to supplement or replace inadequate farm income from land repeatedly trampled on by armies, especially in bad seasons.

One or two other events also likely contributed to the origin or growth of reiving. Aside from the impact of bad weather alluded to above, there is the Black Death. There was a major outbreak in the mid-1400s, resulting in significant loss of life and economic damage. In addition, in 1455, the fall of the most powerful family in the borders, the Black Douglases, created a power vacuum. As a result, other family names sought to extend their influence through raiding and land acquisition.

But as war and skirmishes between England and Scotland continued over the centuries, so the reiving economy became embedded. Reivers planned raids to seize as much movable wealth as possible, cattle, horses, and sometimes prisoners. Often, raiders or the raided were injured or even killed, but pitched battles were avoided if possible. In effect, armed raiding became a core livelihood.

And out of this raiding economy grew systematic “black rent” or blackmail, regular payments in cash or kind extracted under threat of violence, which functioned as an informal tax. Powerful riding families used their control of armed riders and access to pasture or drove routes to sell “protection” to weaker neighbours, making the very insecurity of the grazing economy a source of income in its own right.

But who were the Reivers?

Reivers and Raids

The Border Reivers were both English and Scottish, drawn from families whose lands straddled or were near the frontier. Their loyalty was not to crown or country, but to kin. There were many families involved, including the Armstrongs, Elliots, Kerrs, Scotts, Grahams, Percys, Maxwells, Nixons, Croziers, Olivers, Johnstons, Bells, Rutherfords, Turnbulls, and Charltons, to name just some.

Their raids tended to follow locally known routes, often, but not exclusively, conducted at night. Knowledge of the terrain, hidden fords, bogs, and hill track, was as valuable as a sword.

They were fast-moving riders, on small, sure-footed horses, carrying just light armour. This consisted of a “jack”, a usually sleeveless garment made from two or three layers of quilted cloth, with small overlapping iron plates stitched between them. On their heads, they wore either a light open helmet known as a burgonet or a taller-looking morion. The lance was their weapon of choice.

The quarry was movable wealth (e.g. cattle, horses, and even prisoners) with minimal pitched fighting. Alliances could cut across the national border, so a surname might raid closer neighbours of its own crown while riding in company with a name from the other realm, reflecting the primacy of kin and profit over national loyalty.

But significantly, reiving was not a role undertaken by a family’s hired help. It involved everyone from the family chief to the tenant farmer, plus others who had pledged allegiance to the family.

Scottish lairds and their noble counterparts in England would, on one hand, enjoy all the privileges granted to a gentleman of standing, such as accepting responsibilities, presiding over court, and similar duties. They would also be called upon to muster men for military service. However, on the other hand, they would augment their family wealth through feuds, theft, and blackmail, riding alongside their own men-at-arms for personal gain.

What’s more, a local laird could have considerable power and autonomy, up to and including punishing those allegedly guilty of crimes on their lands.

Alongside the “gentlemen reivers”, family members and those who had pledged allegiance, were those individuals officially classed as outlaws by the authorities. Being outside the law, they had no legal rights or protections. Referred to as broken men, they often sought sanctuary among the various riding families.

Reiving took place all along the Anglo-Scottish border, and raids could push deep into England or Scotland. But Liddesdale and the Debateable Lands were particularly notorious hotspots, as was Tynedale in England.

The debatable lands were so-called because they were claimed by both the Scottish and English Crowns, and populated mainly by powerful Border riding families. These included the Armstrongs, Johnstons and the Grahams. The Crown’s effective authority, on either side, was weak here, and local families governed themselves by their own codes of conduct and vengeance.

Similarly, Liddesdale was a hub of activity for the Armstrongs and the Elliots. Both families earned a notorious reputation, and the violence linked to their raids, along with official efforts to dismantle both families, cemented Liddesdale’s status as the bloodiest valley in Britain.

The geography of the borderlands also helped to shape the reiving culture. The rolling Cheviot Hills, the marshes of the Solway, and the many tangled forests, for example, offered both refuge and routes for swift escape.

As the raiding continued, Peel towers (fortified tower houses) and Bastle houses (sometimes called pele-houses) rose from the landscape. These sturdy, stone-built fortresses were designed not for grandeur but for endurance against sudden attack. These were the homes of the lairds and the better-off farmers. The ordinary folk usually lived in clay and straw-made homes that could be rebuilt quickly if destroyed in a raid. (Towers and Bastles are covered here on the page “Fortresses of Survival“).

A typical raid might start at a designated rendezvous point, known to the raiding party and possibly marked by a cairn or standing stone. Scratches on a post or tree would indicate the direction of travel for latecomers. They would assemble riding their small Galloway ponies, which were swift, agile, and capable of navigating through bogs and across moors.

The raiders would use stealth to approach their target and take as much livestock as possible during the hours of darkness, aiming to avoid any alarm, delays, and reprisals. However, sometimes their target might be a tower house, so they might employ scaling ladders to breach a barmkin wall and then attempt to smoke out those inside the tower or outbuildings. Wooden gates, on the other hand, might be breached by fire.

Knowing the terrain and routes through the valleys, the raiders would herd the plunder, often cattle, and any horses as a bonus, to their own land. They might even leave some of their party to ambush anyone in pursuit.

Sometimes a large-scale raid might be undertaken. In 1593, around 1000 riders, made up of Armstrongs, Elliots, Crosiers, Irvings, Johnstons, and Murrays, carried out a daylight raid on Tynedale in a defiant show of Reiver unity. But many raids involved just a handful of riders.

Feuding

Alongside the reiving culture was one of feuding. The difficulty of securing proper justice led families into feuds. This feud culture was rooted in the idea that an insult or injury to one dishonoured the entire family name, and required either compensation or retaliatory violence. If a man was slain, regardless of the circumstances, his family would avenge the death. In effect, it became the duty that was handed down from father to son. It is therefore not surprising that feuds could last for generations.

This resulted in chains of raid and counter-raid, which would continue unless resolved through agreement, marriage alliance, or intervention by a powerful patron or warden.

Many family names feuded, the Maxwell-Johnstone feud being particularly violent. But perhaps the most famous border feud was between the Scotts and the Kers (sometimes spelt Kerr). It began at what became known as the Battle of Darnick in 1526. A large contingent of Scotts, Elliots and Armstrongs clashed briefly with the 6th Earl of Angus, Archibald Douglas. The aim was to free the young King James V from Douglas influence. Angus was backed by the Kers and Humes.

The Scotts were repelled, but one of their supporters killed Sir Andrew Ker, sparking bitter enmity between the families. Despite attempts at reconciliation through marriage, the attacks on each other continued for the best part of a century. During one such attack in 1550, the Kers set fire to properties belonging to the Scotts, burning the elderly mother of the Scott family’s Laird. The bitterness reached a crisis point two years later. Until then, the feud had been confined to the border region. But in Edinburgh in 1552, a party of Kers came upon family chief Walter Scott (Wicked Wat) and murdered him in the street.

The feud continued, off and on, for the next 50 years or so. The marriage between Janet Scott, sister of the Scott family chief, and Sir Thomas Ker of Ferniehirst (the other main branch of the Ker family) may have eased tensions. But the long‑running hostility only really ended after the Union of the Crowns in 1603, when pressure from a more centralised monarchy made such private warring increasingly unacceptable.

The Marches and the Law

Against this backdrop, Border communities operated in a zone where neither Edinburgh nor London could or would guarantee effective protection of life and property.

March Law instead governed both sides of the border, a framework of custom and practice agreed by Anglo‑Scottish commissioners in 1248 to regulate cross‑border crime and redress. In practice, its purpose was not to eliminate raiding altogether, but to keep a lid on it through recognised procedures for reprisals and compensation.

Nor did it replace the ordinary laws of Scotland and England, but instead functioned alongside them. But given the culture of the Borders, ordinary laws were not particularly effective.

The Marches, three zones on each side of the border, each had a crown-appointed warden whose job was to enforce March law. What’s more, Liddesdale was regarded as so difficult to control that a special “Keeper of Liddesdale” was appointed with the same powers as a Warden.

A warden’s role was to guard and muster the March’s forces at times of war, pursue thieves and fugitives into the opposite realm, and meet with their opposite number to hold courts, hear complaints and enforce decisions.

In practice, Wardens were expected to administer and interpret the law with the minimum assistance from either Edinburgh or London. So a warden could exercise whatever justice he thought fit, and with a perpetual lack of resources, collecting evidence against the accused was a luxury. Put another way, the warden could employ rough justice when it suited.

Wardens on the Scottish side were often powerful local lairds whose own kin and followers might be the worst reivers. This made them crucial intermediaries but also chronic compromisers of the system.

This apparent contradiction lay at the heart of Border society. The Scottish crown lacked the means to impose order directly, so it relied on those lairds with direct experience of the Borders culture.

They were a natural choice because they

- Controlled key routes through the borders

- Could raise large numbers of mounted fighting men at short notice

- Understood Border customs, feuds, and March law intimately

This made them indispensable, even when they were violent and troublesome.

On the other side, English wardens were often outsiders, especially during the latter part of the 16th century when experienced military officers were recruited from the southern counties of England. Their training and skills helped to strengthen their positions, but equally, they sometimes failed to understand the people living along the borders.

A particular problem was the borderers’ willingness, English and Scottish, to make common cause against authority.

So March Law operated to a greater or lesser extent depending upon many circumstances, not least the tenacity or otherwise of the individual wardens.

However, a particular feature of March law was the truce day.

Held near the Border, often at neutral meeting points, the purpose of a Truce Day (or tryst) was to resolve disputes, exchange prisoners, and administer justice under martial law. All hostilities and feuding were suspended. They were attended by the March Warden and an armed following, from either side of the border. This might include leaders and other prominent players from the riding families, as well as those seeking justice, witnesses and prisoners.

The decisions taken on a truce day might include:

- Return of stolen goods or payment of their agreed value.

- Delivery of named offenders for punishment by their own Warden.

- Exchange of hostages or pledges from kin‑groups or surnames to guarantee future good rule.

Despite underlying tensions, these gatherings also allowed for socialising, trade, and even friendships across the frontier.

Another unusual feature of March law was the “Hot Trod”. This was where those who had been robbed during a raid were permitted to pursue their stolen property across the border in an attempt at recovery. It had to proceed with “hound and horn, and hue and cry”. It is said that a piece of burning turf (probably peat) on a spear was carried to openly announce their legitimate purpose. However, the significance of this may have been exaggerated with the passing of time.

Perhaps not surprisingly, given the limitations of the March law, families often looked to their own surname leaders for protection and justice, with private vengeance and compensation becoming common ways to settle disputes over injury, theft, and killings.

So to outsiders, the Reivers were villains. But to their own kin, they were defenders, providers, and symbols of resilience. Their reputation was carried in ballads and stories, painting them as both ruthless marauders and cunning survivors.

The Rough Wooing

A particular practice of this period, when it suited their purpose, was the inducement by the authorities, for certain families to raid each other.

This was a tactic used not just by wardens but sometimes by the crown. And it reached new heights during the war of the Rough Wooing from 1543 to 1551. This was when King Henry VIII of England sought to enforce a marriage alliance between the infant Mary, Queen of Scots, and his own son. Incensed at Scotland’s refusal to go through with the marriage, he sought to terrorise the Scots into acceptance.

He did this through the systematic burning and destruction of towns, villages and communities in the borders, as well as Edinburgh and parts of the Lothians. He carried this out with the help of the English wardens and reivers from both sides of the border.

To enlist Scottish families, threats and inducements were made, with any ongoing feuds being exploited to encourage raids on rival families. Those who gave assurances to England were spared any destruction of their own lands. They became known as Assured Scots. Some received pensions from the English crown, although a smaller number readily joined the fray in support of the Protestant faith against what was still largely Catholic Scotland.

The English wardens, and in particular, Sir Thomas Wharton, secured the services of the Armstrongs, Croziers, Davidsons, Pringles, Taits, Youngs, Turnbulls, Olivers and others. With the help of these Assured Scots, the English were able to burn the borders to an extent never before seen. And with the borders effectively in English hands, Scottish reivers were continually recruited to the English side.

But some Scots were more reluctant to give assurance. Andrew Ker of Ferniehirst and Walter Ker of Cessford took at least three months after their capture before finally providing assurance. However, once assured, they both turned against Walter Scott of Branxholme, raiding whenever they could to continue their long-standing feud.

But the nature of the reiver was such that their loyalties to any particular crown were dependent upon some advantage to themselves. So during the Battle of Ancrum Moor in 1545, those Scots in the English ranks, upon reading the direction of the battle, tore off their red crosses of St. George and turned on their English allies.

However, the war continued for six more years, even after Henry VIII died in 1547. By the end of that year, it was estimated that, led by their lairds, as many as 7000 Scots served England, mostly driven by survival or profit. That said, surviving records only list the names of 950 Scots who interacted with the English.

Interestingly, the oath taken by the Assured Scots changed over the period of the war. In 1543, the oath was for loyal and good service with England against its enemies. However, by 1547, the oath required the assured men to serve King Edward VI (who succeeded Henry VIII), to renounce the Bishop of Rome, and do all they could to further the King’s marriage to Mary.

As the war entered its final years, the Scottish government began taking action against those who had made assurances. Some were found guilty of treason and hanged. But other methods were also employed to persuade the assured to forsake England. Bargains were struck for loyalty, and later, remission was offered to all who would switch sides and fight the English. Andrew Ker of Ferniehirst, captured by French forces who were now supporting the Scots, was among the first to seize this opportunity, vowing to turn all of Teviotdale against their former masters.

The number of assured gradually fell away, and once the war was over, proceedings against collaborators fell off sharply. Some fled to England, but many were pardoned. However, they still faced the prospects of counter raids from those they had plundered while in the service of the English.

Rough Justice

Other than during times of war, the authorities repeatedly attempted to clamp down on reiving. Many of these were organised by Wardens, particulraly from the English side of the border. But more often than not, these amounted to cross-border raids on riding families such as the Scotts, Armstrongs and Kers. In practice, they were indistinguishable from any other raid, and many incursions would have enlisted the help of other Reiver families. And just like other Reiver raids, they resulted in burned property, prisoners and plunder, and perhaps even killings.

Sometimes a raid might also result in a hanging or two with little or no justification for such a final punishment. Indeed, Jeddart Justice, the execution of a person before consideration of the evidence, was widespread.

In Scotland, one notable effort to curb reiving involved King James V, and led to the demise of the infamous reiver, Johnnie Armstrong of Gilnockie. This incident has been covered in a previous post about The Border Reivers of Mangerton Tower. But to jump quickly to the point, Johnnie and his men were hanged. It was at the time quite a blow to the Armstrong family, who were previously thought to be untouchable. However, it set that family against the Scottish crown for the next 80 years.

Sometimes, a warden would seriously overstep their responsibilities. In the 1590s, Kinmont Willie Armstrong was well known to both Scottish and English authorities for cattle theft, raids, and general lawlessness. On 17 March 1596, Kinmont Willie attended a Day of Truce at the Scots’ Dyke near the border. After the meeting concluded and he was riding home towards the Scottish side, he was seized by English officers, under the leadership of Sir Thomas Scrope, Warden of the English West March.

What led to his capture is unknown, but it was a serious violation of March law, which explicitly forbade arrests during or immediately after truce days. Willie was taken to Carlisle Castle and imprisoned.

Walter Scott, the Keeper of Liddesdale and known as the “Bold Buccleuch,” initially attempted diplomacy to free Kinmont Willie. But when this failed, he organised a party of reivers, including some English allies, to rescue Kinmont Willie from his prison. Under the cover of darkness, they broke into the castle, subdued or locked up the guards, and quietly extricated him without killing anyone. An embarrassed Thomas Scrope led a retaliatory raid into Annan and Dumfries, escalating the diplomatic row that followed. The raid itself became legendary and was commemorated in the border ballad Kinmont Willie.

The Curse

A mix of religious duty, social frustration and political pressure led to a somewhat unique effort to curb or punish reiving. It came from Gavin Dunbar, the Archbishop of Glasgow. In October 1525, he issued a dramatic ecclesiastical sanction known as the “Monition of Cursing”. It was aimed at deterring the reivers by threatening them with excommunication and damnation unless they abandoned their lawless ways.

It was read aloud from the pulpits of every parish church in the Borders and also proclaimed at market crosses and other public gathering places. Priests were required to read it to their congregations, making it a region-wide ecclesiastical broadcast.

The curse was in late Middle Scots and went into excruciating detail, cursing the Reivers’ bodies, actions, families, animals, crops, and goods from head to toe. Because of its length and completeness (running to well over a thousand words), it’s often dubbed the “mother of all curses”.

Here is a short extract:

I curse their head and all the hairs of their head; I curse their face, their eyes, their mouth, their nose, their tongue, their teeth, their chin, their shoulders, their breast, their heart, their stomach, their back, their belly, their arms, their legs, their hands, their feet, and every such like part of their body from the top of their head to the soles of their feet, before and behind, within and without.

A later section says:

I sever and divide them from the Church of God and deliver them alive to the devil of hell… forbidding all clergymen to hear their confession or absolve them of their sins until they are absolved of this cursing.

Unfortunately for the Archbishop, the borders were so detached from central authority that the curse was reportedly treated with “amusement rather than fear” by many Reivers. They were largely indifferent to ecclesiastical penalties and continued their raids and feuds unabated.

The Riding Times

In the second half of the 16th century, despite relatively better relations between England and Scotland, incidents of reiving actually increased. In part, this may have been a response to the economic devastation caused by the “Rough Wooing”, such that raiding became a necessity for survival. But equally, a continued weak central authority left the main riding families in control. These decades have been called “The Riding Times”.

Throughout the latter half of the century, there were major Scottish raids into Tynedale, Redesdale, and Northumberland. Not surprisingly, there were retaliatory raids into Teviotdale and elsewhere by English reivers.

But political conflict was never far away. The Marian civil war (1567 – 1573) in Scotland drew in a number of Scottish riding families to a greater or lesser extent, while allowing the border culture to flourish.

To complicate matters, in 1569 a rebellion broke out in northern England aimed at restoring Catholicism and replacing Elizabeth I with Mary, Queen of Scots. It had fallen apart by 1570, and as a result, Elizabeth’s response included raids into Scotland. She targeted Scottish lairds known to have helped shelter the rebels including Scott of Buccleuch and the Kers .

But the most serious Anglo-Scottish clash of the Riding Times occurred in 1575 during a truce meeting at Redeswire (Red Swire). It began when the English Warden, Sir John Forster, failed to produce an accused man to appear and answer for his crime. At some point, Forster is believed to have openly insulted Sir John Carmichael, the deputy warden of Scottish Middle March and Keeper of Liddesdale. Tempers flared, and words turned to weapons.

The men from Tynedale fired a volley of arrows at the Scots, but when more riders arrived from Jedburgh, the now reinforced Scottish contingent fought back, killing the deputy English warden Sir George Heron and taking Forster and others prisoner.

Not surprisingly, this caused a diplomatic row, and Forster was soon released. But it could have been so much worse. Both crowns had reasons to keep the peace. England feared French influence in Scotland, and James VI wanted Elizabeth’s goodwill and, ultimately, her crown.

However, the Raid of Redeswire showed that the Border system could still produce violence capable of triggering international war, and that only political restraint, not law, prevented it.

The End of Reiving

As we know, none of the many counter-reiving operations, whether officially sanctioned or not, resulted in breaking the reiving culture. But on 24 March 1603, the beginning of the end was triggered.

On this day, Queen Elizabeth I of England died, leading to James VI, King of Scots, also becoming James I of England. Following the Union of the Crowns, James moved swiftly and deliberately to end reiving by transforming the Anglo-Scottish Borders from a lawless frontier into what he renamed the Middle Shires.

Crucially, the dynastic union removed the political ambiguity that had long sustained reiving: border families could no longer exploit rival monarchs or shifting loyalties. James imposed unified royal authority by abolishing the old March law and appointing royal commissioners and sheriffs answerable directly to the Crown, often backed by English and Scottish troops acting together.

He combined ruthless repression with legal and social reform. Known reivers were pursued relentlessly; many were executed, imprisoned, or transported to Ireland or the Low Countries, while entire surnames were declared “broken clans” and stripped of legal protection. The Grahams, the Armstrongs, the Elliots and the Nixons felt the full force of this approach.

Over the coming years, the king dismantled fortified towers, confiscated weapons, and tightly controlled the carrying of arms. At the same time, James encouraged economic normalisation by promoting settled agriculture, enforcing debt repayment, and integrating the Borders into the wider systems of English and Scottish law.

The pacification was not gentle, but it was effective. By removing the conditions that had allowed reiving to flourish: weak authority, divided sovereignty, and rampant retaliation, James replaced centuries of endemic violence with centralised justice, permanently altering the character of the Borders within a single generation.

But some family chiefs survived. This was no accident but the result of political usefulness, timely submission, and their ability to recast themselves as agents of the new order rather than relics of the old.

Walter Scott, 1st Lord Scott of Buccleuch (The Bold Buccleuch), and more decisively his successor Francis Scott, grasped early that the Union of the Crowns had ended the old Border game. The Scotts had long been violent and formidable, but they were also indispensable: their kin network was vast, their authority over Teviotdale and Liddesdale unmatched, and their loyalty, once secured, was more valuable to James than their destruction.

Buccleuch offered unequivocal submission, assisted in the suppression of reivers (including his own name), and accepted royal justice where earlier lairds would have resisted it. In return, the chief line was preserved, later rewarded with offices, pensions and advancement, culminating in the creation of the Earl of Buccleuch in 1619. James effectively co-opted the head of the family to police the very society he had once dominated.

The Kers of Cessford followed a similar path. Robert Ker, later 1st Earl of Roxburghe, was already a crown servant and diplomat before 1603, with experience at court and a reputation—by Border standards—for restraint. The Kers had been Wardens of the Middle March and had long acted as intermediaries between Crown and Borders. After the Union, Cessford aligned himself firmly with royal authority, using his influence to restrain his surname and support the commissioners of the Middle Shires.

Remembering the Reivers

Today, the reivers might be long gone, but their family names are not. There are still plenty of Kerrs, Armstrongs and Scotts to be found in the borders and beyond.

Nor have they been forgotten. We celebrate them in events like the Hawick Reiver festival and the Common Ridings, the museums, the memorials, and, of course, in the Border Ballads that survive to this day.

And while many of the historic haunts of the reivers have been lost to time, plenty more can be seen up close, keeping our connection with the past and our heritage alive. From fragmented ruins to restored tower houses, remnants of the reiving era exist throughout the borders. Importantly for me, many have been covered on this website.

Further reading

Alistair Moffat, 2007, The Reivers (Birlinn)

George MacDonald Fraser, 1989, The Steel Bonnets (Collins Harvill)

Godfrey Watson, 1974, The Border Reivers (Robert Hale and Company)

Keith Durham, 1995, The Border Reivers (Osprey Publishing)

Marcus H. Merriman, ‘The Assured Scots: Scottish Collaborators with England during the Rough Wooing’, Scottish Historical Review, 47:143 (1) (April 1968)

Bagtown Clans, 2025, Scotland’s Border Reivers (Rigby Publishing)

Leave a comment