Today, little remains of Mangerton Tower—only a section of the basement and some wall fragments. It is hardly a romantic ruin. Yet, it holds nearly legendary status because of one family: the Armstrongs, infamous and powerful border reivers, who made it their main seat.

The ruined tower sits on the east bank of Liddlel Water near the border town of Newcastleton. In the 1500s, reiving and counter-reiving was a way of life along this stretch of the border. No surprise then that Liddesdale was called “the bloodiest valley in Scotland”. But it wasn’t just Liddesdale that was under Armstrong influence…

Armstrong strongholds, similar to Mangerton, were found in “the Debatable Lands,” as well. This was the neighbouring border area, roughly between the rivers Esk and Sark, extending north of Carlisle towards Canonbie, Teviotdale, and Liddesdale.

Look out for a future episode on Mangerton Tower in the podcast series “Hidden Histories of the Scottish Borders”

The debatable lands were so-called because they were claimed by both the Scottish and English Crowns, and populated mainly by powerful Border riding families. Besides the Armstrongs, these included the Johnstons and the Grahams. The Crown’s authority—on either side—was weak here, and local families effectively governed themselves by their own codes of conduct and vengeance.

From Mangerton, the Armstrongs could muster large numbers of riders for their raids. They would carry out cattle theft, blackmail (known as black rent) and cross-border attacks, often striking deep into England.

But the Armstrongs’ reiving activities brought repeated violence to Mangerton Tower. It was a primary target for any force—English or Scottish—seeking to impose order on Liddesdale. The tower was sacked in 1523 and burned to the ground in 1543, only to be quickly rebuilt each time.

But the most dramatic destruction came in March 1569 when Regent Moray stayed at Mangerton Tower itself before ordering it blown up with gunpowder. According to historical accounts, the tower remarkably “withstood the initial shock of the gunpowder explosion” and was repaired soon afterwards.

Every rebuilding was an act of supreme defiance, reflected in the Armstrong motto: Invictus Maneo (I Remain Unvanquished).

The Armstrongs operated as a coordinated family network, often raiding together from their other towers and strongholds, notably Gilnockie Tower (also known as Hollows Tower) and the Tower of Sark, both in the debatable lands.

Their reputation was so formidable that they were considered virtually untouchable in the Borders until King James V of Scotland moved against them in the 16th century.

The younger brother of Thomas Armstrong of Mangerton was one Johnnie Armstrong. A particularly notorious figure from Gilnockie Tower. His numerous cattle thefts and acts of extortion were an embarrassment to James V, who was determined to break the Armstrong family’s power. So the king invited Johnnie Armstrong to a meeting at Caerlanrig under a promise of safe-conduct.

When Johnnie and his followers rode in, dressed in magnificent armour and fine velvet, the King was not impressed by their loyalty but infuriated by their grandeur. The display of wealth was, to him, a public act of disrespect. He is famously said to have cried out, “What wants yon knave that a King should have but the sword of honour and the crown?” There was no trial, only a swift, cold order for execution.

Johnnie Armstrong and his men were hanged. This betrayal, which involved the brother of the reigning Laird, turned every man in Liddesdale against the Scottish Crown and ensured that defiance would be the Mangerton Armstrongs’ enduring policy for the next eighty years.

One act that underlined their defiance was the 1593 Tyndale Raid, led by Archibald Armstrong (Laird of Mangerton and Armstrong chief), Kinmont Willie Armstrong, and William Elliot of Larriston. They assembled a force of approximately 1,000 horsemen drawn from Liddesdale, Eskdale, Annandale, and Ewesdale—an alliance of riding families rarely seen on such a scale that included Elliots, Crosiers, Irvings, Johnstons, Murrays and Scotts.

In broad daylight, this host rode into Tynedale in Northumberland and carried off 1,005 head of cattle, 1,000 sheep and goats, 24 horses and mares, burned at least one farmstead and a mill, and stole £300 sterling in household goods or “insight gear”. The raid was highly provocative, breaking with the convention of nighttime raids.

It was a calculated show of power and defiance precisely because at the time, the political climate was shifting, and the Reivers’ way of life was under threat. Indeed, King James VI was positioning himself to take the English crown, and so increasing pressure on the Border families through enforcement action.

The scale of the raid, and its occurrence during daylight, provoked alarm and outrage among English authorities and local populations—a clear challenge to royal power and Border officials. Local English communities were devastated, suffering significant economic losses and widespread fear of further incursions.

The raid, in the short term, strained Anglo-Scottish diplomatic relations and led to increased pressure on both crowns to pacify the Borders. What followed was the beginning of the end for the Armstongs. Their great gamble, a massive show of Reiver solidarity and strength, failed to derail the united efforts of both governments to suppress the Border families.

But reprisals were not immediate. However, the imprisonment of Kinmont Willie Armstrong, captured on a truce day in breach of the March law, and his subsequent escape, added fuel to the fire.

The Marches were the six frontier districts, three on each side of the border, each responsible for defending and policing its section of the often-turbulent boundary. Each had a crown-appointed warden whose role was to oversee their specific March and enforce March law, a pragmatic cross-border code mainly based on custom and practice. On “Truce Days”, gatherings attended by Wardens and Reiver families from each side of the border listened to formal complaints and reached verdicts. During the truce, all participants were granted safe conduct—wrongdoers could not be arrested, and feuding had to cease.

Kinmont Willie had been imprisoned in Carlisle Castle. The English warden of the West March, Thomas Scrope, was holding him in the hope of securing some pledges of good behaviour and gaining influence over the Keeper of Liddesdale in the Scottish Middle March, “Bold” Scott of Buccleuch (a role that held the same rank as Warden under James VI).

But Buccleuch led a daring raid with a small band of Reivers, aided by English Graham’s and Carletons, and broke him out of Carlisle Castle. Scope was said to have been beside himself with rage, and he directed his vengeance at those in Liddesdale and the Debatable Lands. The most vicious attack took place on the banks of the Liddel near Newcastleton in 1596.

Soldiers burned every home along a four-mile stretch of river, took the men prisoner and stripped women and children of their clothes, leaving them exposed to the weather. This was Armstrong territory so they likely took the brunt of this attack.

That same year, Robert Carey was made warden of the English Middle March. Rather than follow Scrope’s “scorched earth” approach, he tried a more thoughtful way of subduing the Armstongs.

In the summer of 1601, he led a small cavalry unit to Liddesdale and established a camp, even building a small wooden fort near the site of Mangerton Tower. Whether forewarned or simply perceiving the threat, the Armstrongs, along with their families and stolen livestock, withdrew to Tarras Moss. This was an area of bogs and scrub, well known to the Armstrongs. Carey planned to encircle the Armstrongs, blocking their escape routes from Tarras Moss and aiming to starve them out. Reinforcements sent by King James VI joined them.

Whether Carey attacked first or whether the Armstrongs sought to break out isn’t entirely clear. But most Armstrongs escaped. However, they left their plundered livestock behind, and this was subsequently returned to its rightful owners.

Ultimately, the Armstrong family survived, but this led to further punitive measures from the authorities. The tower at Mangerton was torched again, and this time it wasn’t rebuilt. Following this destruction, the Armstrongs’ power in the Borders rapidly declined.

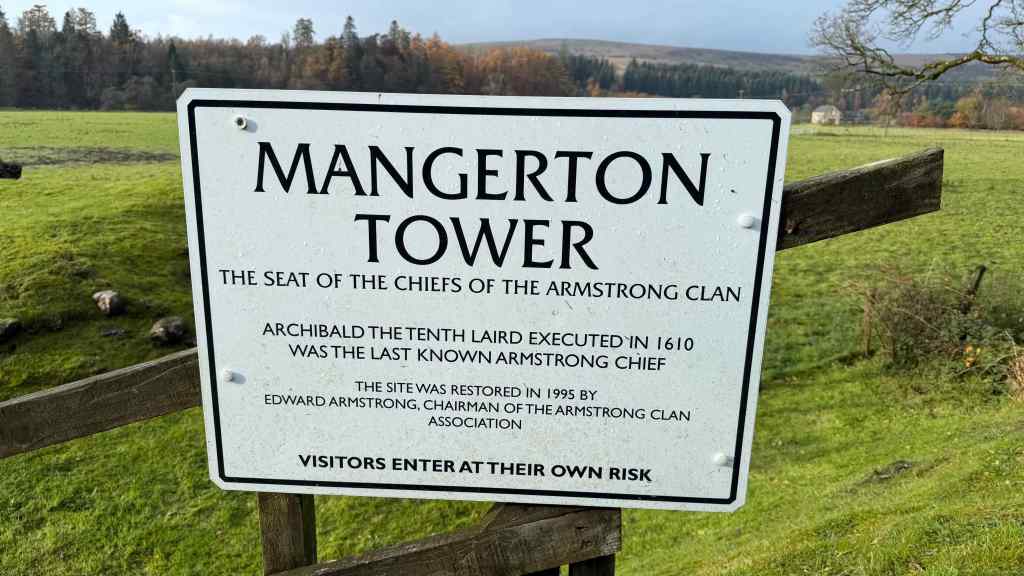

The unification of the Scottish and English crowns in 1603 was followed by the end of March law, the forfeiture of Armstrong lands, the outlawing of individuals, arrests, transportation, and hangings. Some family members fled to England or abroad. Archibald Armstrong, the last of the Armstrong lairds of Mangerton, was hanged in 1610 for raiding Penrith in England and stealing cattle.

Essentially, James VI and I’s pacification of the Borders dismantled the very social, economic and legal bases upon which families like the Armstrongs had thrived.

Today, Mangerton Tower is just a mix of turf and broken walls. But in its day, it was a tower that was approximately 11 metres by 8.5 metres in dimension, with walls over 1.6 metres thick.

The Armstrong Clan Association restored the site in 1995. What remains can be viewed easily by crossing the river from the main street in Newcastleton. Then follow the minor road south for about 500 metres and turn onto the track (the old railway line), taking you past the holiday cabins. Continue for another 500 metres, and the tower is located on your right, just below the embankment.

There may not be much left to see, but Mangerton Tower has a violent and colourful history. The stories of the Armstongs have passed into legend, but they continue to fascinate anyone interested in Borders’ heritage.

Mangerton Tower: OS National Grid Reference NY 47975 85340

Further reading

Graham Robb, 2018 The Debateable Land (Picador)

Mike Salter 1994, The Castles of Lothian and The Borders (Folly Publications)

Tom Moss, Border Reivers, Rose Cottage Publications

Leave a comment